Richard Patterson

“The YBA thing wasn’t exactly a movement, but it was the last and closest thing we’ve had to a movement in recent times where a whole crop of artists emerged together apparently responding to a mood and sequence of events.”

Interview by: Natalia Gonzalez Martin

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your background? Where did you study?

I grew up in Hertfordshire, England with my mum, dad, and three brothers. My father worked in London as the pensions’ manager for GEC-Marconi – my mother had been a teacher before having children and then devoted her life to the family– Of my brothers, two are involved in writing – Philip is a literary agent, Julian is a journalist/PR person and Simon is an artist as well.

After leaving school, I went to Watford College of Art for a one-year foundation course, before going to Goldsmiths’ in London.

I’d say I learned most of what I needed to know about art in terms of how to actually paint and how to look at things prior to going to art school, with much of it coming from my junior school experiences.

No one taught me how to paint at Goldsmiths’. It wasn’t that sort of place. The tutors were professional artists and by being around them, you picked up how to develop and work through ideas. It accelerated what might have taken nine years to learn in the outside world into a three-year course. A kind of lifemanship for artists, if you like.

Perhaps the main thing I took from Goldsmiths’ was from Michael Craig-Martin – which was the importance of trusting intuition and his feeling that the unique talent that any given artist has is often innate, so much so that it becomes invisible to themself. In this regard, the importance of having smart and creative people around you that value what you do but you sometimes can’t see is paramount.

That sunny dome! those caves of ice, 2015

Christina with Dutch Door, 2015

There is a layering aspect in your work that is inherently digital, how does technology influence your work?

I think mostly this comes from being steeped in music early in life. My father had an incredible collection of classical records and music was always in the house. I like the aspect of music that it can have many voices that come together to make a whole but that can still be heard separately. Painting can’t really do this – although cubism tried to achieve this, but it doesn’t mean it’s not always at the forefront of the mind as a paradigm for an ideal painting.

I wish I could banish digital technology from my work process altogether. It’s not how the work came about initially. My work was entirely analogue – the only technology involved was photography. Other than that, it was glue and scissors, paint and canvas, but it was suggestive of the technology that was about to be upon us. Now I use photoshop to compose in, and some of the imagery I use comes off the internet – but digitalization has its issues; it’s an affliction almost. I want my paintings to be of the “wind-down windows” variety, not the “Sat-Nav” screen variety. Eventually, there will be the equivalent of the slow food movement where people learn not to use their computers and throw their i-phones down the garbage disposal unit. Hopefully. More likely we’re destined to have our brains hard-wired to computers.

The problem for me with the digital tech is that it has no natural limits and no natural dynamics. As a tool, it has no character. Many people like its scope and flexibility, but for me, it’s too infinite. Michael Craig-Martin once said to me as a student at Goldsmiths’ “Your problem is, you don’t have a problem”. Nothing is problematic on a computer. It risks being inert, therefore. My student problem of not having a problem is now everyone-who-has-a-computer’s problem. Making a painting has physical limits – drying times of paint, for instance. It’s an organic thing that you have to keep alive while you’re making it.

The paintings that I first showed in London were layered in one of two ways: either I was distorting or covering a small object of figure with globs of paint that changed the objects form as well as its colour, then scaling it up and making it into a large-scale rendering of that object; or it was a collaged image made old-school with scissors and glue. These have their roots in Kurt Schwitters, Rauschenberg, Picabia, Picasso, Braque, late de Chirico, Dieter Roth, and others rather than any new technology.

Your technique has strong classical and traditional elements, what artists and imagery do you find inspiration in?

My parents hung those somewhat expensive reproductions of well-known artworks mounted onto a type of black particle board in their house when I was growing up. I remember them all vividly – a Picasso gouache of his son Paulo as Pierrot leaning on a chair, a Turner riverscape, a Turner seascape, the Renoir Boating Party, a Vlaminck landscape, a Hogarth etching reproduced on a silver plate. Meanwhile, I was at a progressive junior school which elevated art, music, and creative writing to the same levels of importance as maths, history, science, languages, and so on. The school also had similar reproductions dotted around the common areas, Van Gogh sunflowers, a Picasso still life with candle, a Brueghel snowscape. I guess these reproductions had a bigger influence on me than I might have realized at the time. Of the paintings at the school, the Breughel and the Picasso were the most compelling.

Inevitably Richter has been a huge and unavoidable influence.

I’ve always admired de Kooning and his whole position. So many painters have tried to emulate him, but none get close. Then many of the usual greats: Bellini, Vermeer, Velasquez. Picasso, Rembrandt, Caravaggio, Manet, Monet. I like painters that have incredible touch, and/or invention, and/or light and/or psychological presence. When I visit somewhere like the National Gallery, it’s these painters that endure and that I tend to come back to. It’s not that I prefer older paintings, it’s just that contemporary painters can age quite rapidly - they’re not always as great as you thought they were ten years on.

In terms of imagery, I don’t have any imagery that is a particular source of inspiration although I do return to certain subjects. The human form is constantly a source of fascination, although I allude to it as much as I directly paint it.

Solo show, Timothy Taylor Gallery 2014

Solo show, Timothy Taylor Gallery 2014

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day/studio routine? What is your studio like?

My day varies depending on whether I’m mid-painting or not. If I’m mid-painting, I arrive, I may check my emails and then I start painting and probably break every ninety minutes or so. Painting requires a lot of focus. It’s physically very tiring. Some days are standard length working days, some can be much longer since I often need to get to a certain point before I stop so that I can continue easily the next day since I paint wet into wet. Often if my working days are overlong, they slip around the clock, but I’m too old to do this now.

If I’m not mid-painting then it’s less routine. Sometimes I already know what the next painting is going to be and sometimes I don’t. Some of the better things I’ve made, I kind of arrive at them with a degree of chance. I hate being in between paintings.

My studio is a unit in the old railway offices of one of the big Texas-Pacific railroads that ran nearby. It’s a grand building probably dating from about 1900. The studio is quite large and with a high tinned ceiling. I live nearby so I can walk to work. I’m very studio-centric. If I’m not there, I don’t always feel like I know who I am. I feel like my paintings look best in my studio. I’m often horrified to see one in someone else’s house or a gallery or wherever. I feel like I’ve been robbed or like I’ve overstayed my welcome. It feels like a bit of a violation.

The art world has had to adapt the ways in which we show work, allowing us to explore the digital realm to do this. ‘The Eye of The Huntress’ provides an immersive experience as an alternative to visiting an exhibition in real life. How do you feel this affects the way in which people interact with your work?

I think I’ll have to wait and see. Much of my earlier work utilized shifts in scale and deceptive or mysterious image quality. The challenge of the virtual realm is indicating the levels of realness and the nuance of surface. Even online, people mistake some of my paintings for photographs of sculptures. I’m thankful to have an outlet in these difficult times, however. It’s interesting that the virtual space is so neutral. It also allows my work to be seen alongside other artists I might not have shown with otherwise. In Eye of the Huntress, for example, my painting is next to a piece by Jim Lambie, whose work I like a lot. Proximity is a fundamental of context.

‘The Eye of The Huntress’ Online Exhibition 2020

You are part of the YBA, what are the main changes you have noticed in the art world from the time when the group was created compared to now?

A massive question that I’m not sure I can answer except in an obvious way – e.g. far more artists than ever before, more galleries, more collectors, more art fairs, more media coverage, but I’m not sure any of this is actually an advancement. As Richter says, art has become entertainment now. I think there’s been a profound change in our culture since the mid-1990s and the YBA period.

It’s very difficult to say whether art has been directly affected by the cultural changes or whether art was on a separate path of change in any case. I think both are true and not mutually exclusive possibilities. I think we’re in an extended period of mannerism. To me - and this is a massive generalization - art now feels more compromised and inevitably repetitious. It’s far more like fashion now. Partly this is the effect of art fairs, partly it’s because of the art itself. Where people used to question something that was deeply derivative as entirely reactionary or stupid, now the recycling of older or redundant forms is like when flares come back into fashion, or high-waisted 1980s jeans. There is much more acceptance now which might almost feel like indifference.

Timelines and historical sequence seem to be more irrelevant now, in a manner that can make art feel detached from a sense of place. The YBA thing wasn’t exactly a movement, but it was the last and closest thing we’ve had to a movement in recent times where a whole crop of artists emerged together apparently responding to a mood and sequence of events.

Clearly, IT has changed the culture as profoundly as the steam engine did in the industrial revolution. The last 30 years have seen massive change, but it’s a kind of soft change, soft revolutions are taking place all around us in insidious ways.

The art world in London was much smaller back in the 1990s during the YBA time, and yet paradoxically it was probably felt larger in a sense, or certainly more potent because I think it was more cohesive. Access was more limited. If you wanted to seek out the art world you had to be very interested in art otherwise the art world was almost invisible.

Access to the art world is maybe different now because the art world is a different thing. Now you just need an app to get in. It also means you have no commitment to it if you don’t want to. It’s like watching tv and flipping channels. I sense there is less of the energy of small knots of artists and creative people that together make up scenes and subsets. I miss the interaction of how it used to be. At every level, you had to make more of an effort and be more ingenious.

Even though contemporary art is everywhere, it feels more decorative at present – some of its purpose; to communicate and bond people in common spaces where they can collectively experience beauty or calmness has been replaced by technological platforms. Art competes with Instagram now.

On the positive side, art feels more democratic than ever before and it comes from everywhere.

The Birth of Jan, 2013

Dr. Soaper, 2016

Why did you move to America and what are the main differences between being an artist there and in the UK?

I moved to America because that’s where I met my wife, Christina Rees. I’d had a fantasy about living in NY or LA since I was about 15 but I never actually thought I’d end up there. We did live in NY for a few years, but we arrived there barely a few weeks after 9-11 and the city was in a state of shock. Too much snow as well, so we moved to Dallas. Everyone thought I was crazy to do it and some tried to make interventions. Even people in Dallas thought I was crazy to move there. I think Dallas is a quintessential and rapidly growing US city, however, and I think it points the way forward for a lot of America.

In terms of being an artist in London vs Dallas, it’s quite different in one important respect – when asked what my job was in Dallas, and I’d say I’m an artist – they’d say, “That’s great - I love art. What’s your day job?” The concept of the professional artist barely existed here when I first arrived. That’s not true of NY. The perception is that important art comes from the outside and is imported in. When I lived in London and showed in Dallas I had a different status to when I moved here full time. You become what’s called a local artist. No one calls you a local artist if you work in NY, even if you’ve never shown your work. It demonstrates a problematic schism in the aspirations of the society here.

Texas has incredible private and public collections, not such great art schools (although, does anywhere have good schools anymore?)

Every day of my life I feel conspicuously British. A shrink told me once that I needed to adapt. And I thought, oh no, I’m going to have to adopt the accent and wear cowboy boots. As it happens, the Texan accent is the nicest on the ear of all of the American accents. But I can’t say sidewalk and trashcan and so on. Actually, I do say trashcan. No one knows what ‘dust bin’ is here.

One of the main themes around your work is painting itself and questioning it as a medium to perceive reality, could you describe some other themes that are relevant in your practice?

I don’t know if it’s a theme exactly, but there is a sense of displacement. This has probably got stronger since I moved to the US, and it’s to do with finding difficulty in being grounded in the culture here. When I first moved to the US I began to realize that despite the fact we speak the same language and Europeans speak different languages to each other, I often felt more affinity with fellow Europeans. I still feel a sense of estrangement here. I think this has been a constant theme, but it’s hard to say how it plays out in the work. There is, for example, a different understanding of the term “irony” in the two countries.

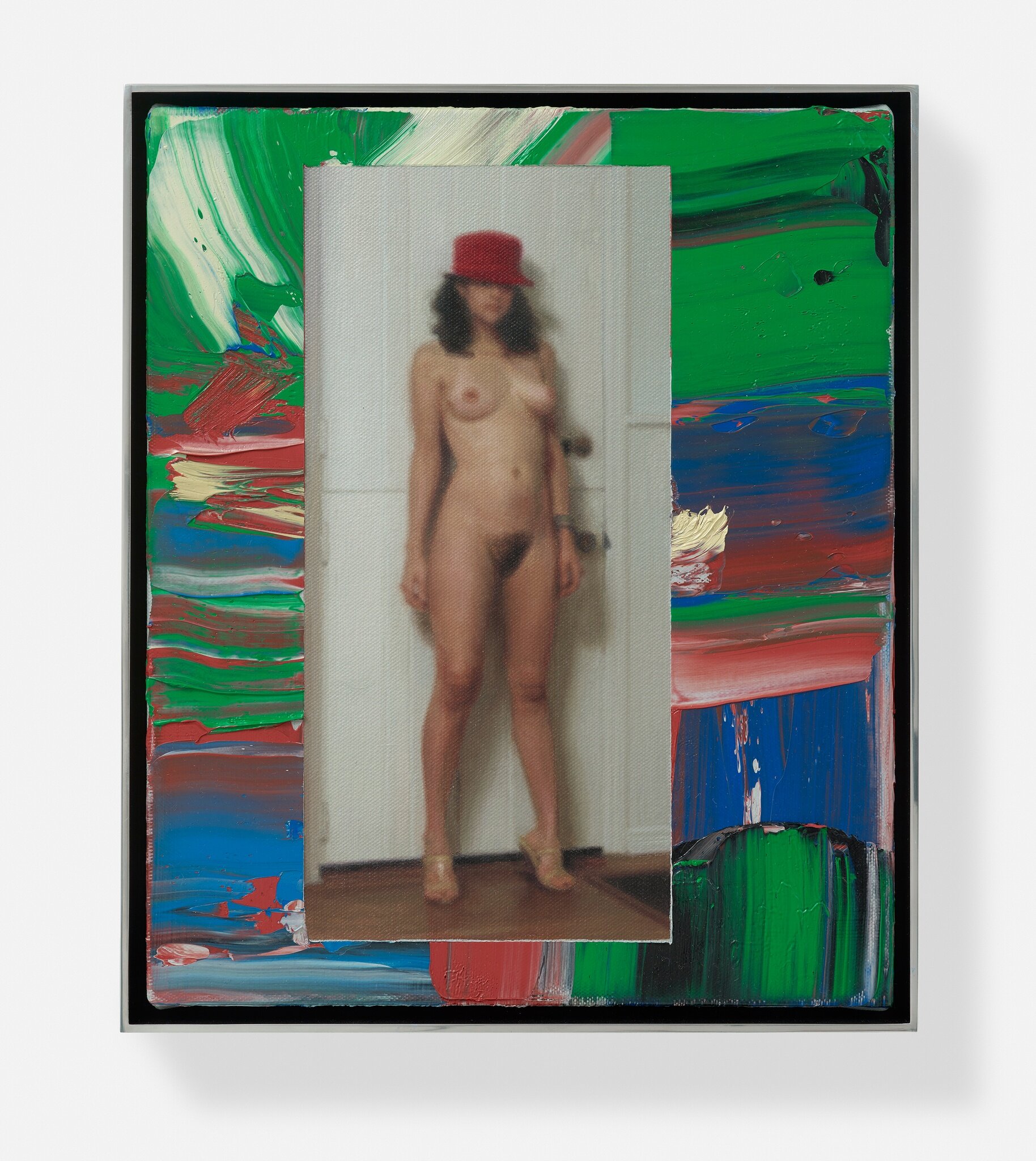

I like what I like to call half-spaces – which is to say, stuff that is either literally or metaphorically in a type of half-shadow. Sometimes these half-spaces are to do with colliding two things that shouldn’t or can’t exist together physically in the real world. I often juxtapose differing painting languages in order to create a duality.

I like the idea of form as colour – like in my paintings that feature globs of coloured paint. Other themes that have cropped up are an expression of various political or social issues, like materialism as expressed in advertising: desire vs sex vs pornography, vs the erotic; masculinity and its debunking in the Minotaurs: the mother/matriarch/sphinx in the various cheerleaders – the cheerleaders were antithetical muses since the culture of cheerleaders seemed foreign to me and very American (I mostly stopped using them once I arrived in the US); golems in the soldier series. I’ve painted Christina quite a few times.

How do you go about naming your work?

Titles just come to me as I’m working since there are all sorts of narratives swirling around my head. If I don’t have a title before the painting is finished, then I sometimes struggle and just call it whatever it is – like, ‘Minotaur’ or something. Quite often, I’m trying to suggest that the painting’s real subject may not be as literal as it appears on the canvas.

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

I haven’t seen any art for ages. I like George Condo’s recent paintings a lot. I’ve been looking again at Richter, Vermeer, and Bellini.

Is there anything else in the pipeline?

An exhibition in Dallas next year.

All images are courtesy of the artist, Eye Of The Huntress and Timothy Taylor

Date of publication: 21/01/21