Lorraine Fossi

Could you tell us a bit about yourself? How long have you been a practicing artist and where did it all begin?

I grew up in Paris into a family of architects; immersed in floor plans and section plans drawn on tracing paper and sketch models since my early years. My father would explain things to me with little sketches and arrows on napkins and tablecloths in cafes. I saw in the drawing a form of writing, and a direct access to information.

At the age of 7 I made this drawing: it is seen from above, an image and a function, features which survive into my work today.

I studied architecture at the Beaux Arts, and by the end of my studies I was convinced that a building should develop from the inside according to its function, and grow along a network of virtual lines developing in space. My professional practice in architecture offices was not creative at all - it was mostly about tracing (repeating) the projects of others, changing the scales and rendering façades with coloured pencils.

I moved to London in 2000 and went to my first proper painting class run by a traditional painter in 2006. I noticed the nice feeling of being focused and relaxed, and I very soon started to draw sketches for new paintings- in the tube, or in my bed. I remember the day when I said to myself: ‘this is what I want’. I was two metres from my surface, looking at a luminous yet tangible yellow green wall. I had painted this; I had transformed my surface into something entirely new.

In 2008 I was commissioned to make a painting of the sea, from which a whole series of work and exhibitions followed. I somehow knew the sea was not my subject, and beside the commercial success of these paintings I decided to let them go. I enrolled in an MA in Fine Art at City & Guilds in September 2013 and graduated in 2015. By the end of my first year at college I let go completely of the idea of representation to produce an abstract work in which the painting is a function – and in which any part of the world could be caught up.

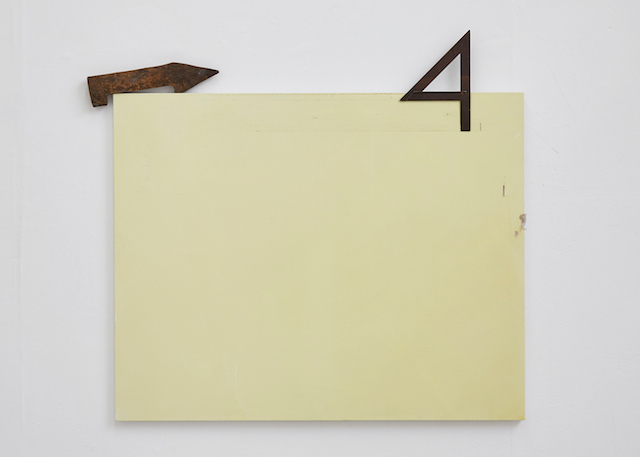

Stetched 2016

Laguna 2015

You use skewed shapes and angles instead of the transitional square/rectangle canvas, could you talk about this and the reasons behind it?

My work is shaped by architectural discourse. The floor plan, the section plan, the upturned view, the perspective view –I am continuously moving in between perspectives. The work starts ‘in experience’: experience of lagoons in Venice, of the game of Pachinko, of the diagram of the street, of things moving along and across limitations. Reality is then undone and transformed in the new territory of the surface support. The shaped canvas embodies the perspective view of someone walking along a street, or flying above the surface. Placed against the wall in a vertical position, it materializes my idea of a surface existing outside the gallery space, in the street, somewhere in the world.

That is why my surface/territory so often refers in colour and texture to the world’s materiality: it is a fragment of the world.

In ‘Flight of the Storks’, for example, the two skewed trapezoid surfaces meet and separate, one becoming the other, repeating but becoming different. It happens the same way for the arrow/ bird shapes, but perhaps not at the same rhythm or time. There are two different diagrams interplaying here, one concerns a territorial enclosure, the other a desire of migration. As with real migrations, elements disappear and reappear, slightly transformed by the journey.

In all these works my decision to use the skewed canvases is not a formal one – it has a function.

Dialogue 2015

Would you say your work is between painting and sculpture? If so, could you talk about this and what attracts you to this way of working?

My work aims to reach a material reality by the use of the diagram: it is a work of assemblage. Sometimes it functions as a sculptural object from a far distance and as a painting from a closer distance.

However, it doesn’t come from a desire to create sculptural pieces but rather from the desire to assemble elements. I choose my materials according to the diagram, from a wide range of materials culled from everyday life and sometimes including ‘found objects’.

In some cases the canvas itself is ‘material’ and the found object becomes the painting’s function. I enjoy objects made to slide, like the T square that I used to push along the edge of the architect’s table in a past life. So a work might embody the shape and the content of the architect’s drawing board, or other times it is a found object that triggers the diagram of a work. The realization of the work comes in experience as a performance in which I re- process reality. It is not a representation of something.

Flight of the Storks (triptych) 2015

What is your process, how do you start a new piece of work?

I make huge numbers of sketches, take pictures, and also look at other artists’ work - always in search of new connections and visual attraction. I don’t copy- I consume; I accumulate. From this gathering of information a new work will emerge. My readings of theory by Deleuze and Foucault are immediately translated into diagram form as well as inducing ideas for new works. My practice suggests a body that is expanding with no beginning and no end, and I will start a new piece while already working on something that is ‘becoming’. This way I keep things with a loose fit, with space between the works. Sometimes a pair is created this way, like two lovers getting closer.

At home, in my kitchen, I will draw and reflect on what is in an unformed state at the studio. In the studio, when I make paintings, I usually use unprimed linen and a gesso primer toned with grey or a light ochre. I sometimes add sand, dust and bits found outside the studio if I want to obtain a sense of material reality. I find objects in every sort of context that become part of the work, or the trigger for a new one. Then my work travels from reality to abstraction, constantly pulling and pushing, and back to the real world within which moments, places, memories and desire reappear – and it becomes something that is new.

Climbing Wall 2016

What do you hope the viewer gains/reacts from looking at your work?

There are many points of entry into my work, and many different perspectives from which to see it. I create a space for myself and for the viewer to imagine moving, measuring, stepping back, and also resting. The viewer will not necessarily recognize a place or a feeling, but sense an inherent logic and become curious. Perhaps it is a perspective line that seems familiar, or the grey colour covered with scruffs and imprints and scratched words, or that blue that could be the sky, or perhaps the sea. Looking at several works, I think the viewer will perceive that my paintings are fragments of some vaster territory, like a huge root system. My dream would to hear from viewers that they recognized my painting in the street, in a story, in the bath or on the news on television.

How do you go about naming your work?

It comes at some point during the making of the work or right after. It tells what the work is (for example ‘Climbing Wall’) or refers to something I have seen or experienced in the past and recognize in the painting. ‘The Flight of the Storks’ refers to the migration of the storks in Alsace in France, yet I think it is obvious that the painting is not about that. It happens that I change title when after some time I understand the work differently. For example the work ‘Sliding’ changed its name to ‘An Instrument of Measurement’. With ‘Block of Memory” it was the act of naming the artwork that helped me to understand what it was.

Drawing Machine 2015

An instrument of measurement 2015

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

There is a work made by Finbar Ward that I saw at Fold Gallery. It was composed of 300 small almost identical shaped canvases, displayed all over the wall of the gallery. The gallery space was included in a work of art and the artist was somehow ‘absent’. Here the assemblage work functions and merges architecture with an art practice. There is the sense of a ‘double skin’ expanding from the walls with a clear intention to create an experience for the viewer. It reminded me the architectural promenade of Le Corbusier in which the visitor would enter, walk, look, feel, then turn and see something entirely new.

Another recently seen work resonates with me, it is a video work made by Mark Wallinger that I saw at Hauser and Wirth. It investigates the notion of repetition and difference using four identical videos running simultaneously. At the center there is a space for the viewer who is watching ‘the same video’ but at a different time. The work has reactivated in me a Deleuzian theory that says that when time is de-compressing, then a difference occurs.

Lastly, I recently went to an inspiring talk with Anna Tallentire at Hollybush Gardens and it brought to the surface all sorts of ideas of work I had somehow forgotten.

Charrette at Turps Gallery 2016

Charrette at Turps Gallery 2016

Charrette at Turps Gallery 2016

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day/studio routine?

I am lucky to live at walking distance from my studio. On the way to my studio I cross a market that occupies an entire road. It is my place of decompression and separation from home and my family. It feels to me like I really need that space. So I walk, looking at the people, the colours, the strange things for sale, absorb some Reggae music, and that’s it, I am at my studio. I am also lucky because I am not sharing my studio. I could not work with others because I work in total silence, no music, radio, no phone calls, no Internet research. I chose a ground floor in a large unit, the direct access to the outside is something I enjoy, not only for the deliveries of works and materials but also because I can step outside, and breathe when it get too intense inside the studio. In my studio I move around, look for things, find things, make a mess, build structures, paint and assemble, working from above like the cartographer, or from straight on like the viewer. At the end of the day the surface records in itself traces of conflicts and transformations, and also a certain pleasure – while on my side it is a total exhaustion! I usually spend 6 to 9 hours at the studio with a small pause for lunch. I always bring chocolate because I trust it has a beneficial impact on my mood and my work. I rarely go two days in the row at the studio because after an intense day of work I need to rest, physically and mentally. On the days I am not at the studio I sometimes make small paintings and drawings in my kitchen, and I go to visit exhibitions and meet people.

What does the future hold for you as an artist? Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

If Britain exits the European Union, well I am not sure it would hold anything good! I’m starting to think what I’ll do; another place I would consider living in is Venice. I want to go make works in Venice anyway and study the wooden pillar’s numerous functions of dividing the surface, directing the boats and creating avenues for the vaporetto. I have another idea for a large body of work that would document the story of a wall that I’ve seen in a small island in Sardinia. The wall divides the town in two distinct territories, holding within it an insidious diagram of control, separation and exclusion. With these, and other projects, I have a lot of work waiting to emerge.

I am presently organizing an Art Salon in my house, having fun with the hanging of a large number of artworks, including work made earlier on, as well as family objects and my own findings. I will not stick to the traditional exhibition format: I am interested in the blurring of art and life!

Otherwise I am waiting for the confirmation of a residency in Taiwan (cross fingers) and will be helping some artist friends with their new gallery and residency space in Putney.

Publishing date of this interview 24/06/16