J Price

"The process is an act of love; like swaddling a child. In a way I hope I am the object, the side with substance."

Could you tell us a bit about yourself. How long have you been a practicing artist and where did you study?

I graduated from my BA at the University for the Creative Arts, then took a few years out doing residencies around the world for four years. I applied for the Masters course at the Royal College of Art for THREE YEARS, before in the third interview asking them, “What do I have to do to get in here?!” They let me in, and I received a full scholarship from Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust to be able to accept the offer. I graduated from the RCA in 2015.

To speak about my work I will have to give you a little back-story. I am a schizophrenic. I have had the wonderful, terrifying and tragic experiences of psychosis; from watching electric lights drip into shadows and being more than the sum of my body, to holding professional conversations while being violently stabbed by hallucinations, or watching friends die when care budgets were cut or due to a lack of clinical staff ‘s understanding and patients/friends societal treatment as beneath human. And I have mourned greatly and in isolation for the loss of my own personal [imaginary] comrades and for a state of mind elegantly tormented when I decided to medicate.

My artwork explores my own questions about where my personality and experiences begin and where schizophrenia and hallucinations ends. I am objectively intrigued about elements of my personality being diagnostic criteria of a disorder; it is both fascinating and disorientating considering characteristics of my individuality or consciousness is a result of a disease.

During psychotic episodes, hallucinations and personality changes I could not help but rationally question whether I was the original: if I the initial personality, or had I appropriated the body and was I in fact a by-product or hallucination. When I medicated was that ‘me’, or the powerful anti-psychotics placing me in a chemical straightjacket where my brain chemistry, personality, and everything that made me who I was, was eradicated? These seem like ridiculous, self indulgent, or even spiritual questions but they weren’t – they were logical, practical questions for me to consider and evaluate.

Yet, moving from the unavoidable prejudiced narcissism of self-portraiture to the notion of the unheard community lead me to revisit activism and collaboration. I am driven to confront the ignorance surrounding psychosis and my impotent frustration with the historical and present day societal treatment of psychotic people.

The invisible have no history, and the indomitable effort to ignore or deny the existence of the insane throughout history has robbed those people of a past, present and future. The diagnosis they were given limited their ability to communicate and the lessons and truths in all they said were cast away. Their work was devalued, as they were as people, and an art sensitive to a viewpoint and experience few will have the chance to know was and is being lost.

I can’t accept that. I have to contribute something honest and real to counteract the Hollywood movies and sensationalized newspaper articles; to enable empathy to challenge imposed dogma.

Soixante-neuf, 2008-9, [borrowed] trolley, ink, curtain lining, 472cm x 238cm

The prints have a ghostly appearance, they remind us of the so called miracle/image of Christ, The Turin Shroud. Could you talk about the technique of placing fabric onto inked objects? How did this first come about?

This style of work first came about because my tv exploded and between myself and two friends we carried it through snow to my studio, where I looked at it for a while. Prior to this moment I had been a predominantly figurative, traditional printmaker, but I had just been through a rather public and embarrassing psychotic break and I could no longer reconcile my work and process with my experiences. I wanted to explore a process that would address some of the questions I had at that time. I ripped down my curtains and stripped out the lining, inked up the television and wrapped the fabric around it, removing it to see the impression left.

I ripped down my curtains and stripped out the lining, inked up the television and wrapped the fabric around it, removing it to see the impression left.

The process is an act of love; like swaddling a child. In a way I hope I am the object, the side with substance. When I strip that impression from the object I want that to be the other people who reside in me. By putting that out for display as an inkblot I am asking the audience what it is, and how to fix it.

I still work with curtain lining to reference this moment and these decisions, though my process has adapted and developed to new questions and later experiences.

The Insides/Appassionata, 2008-9, object, ink, curtain lining, 167.4cm x 238cm

Cars, shopping trolleys and pairs of glasses are used for these prints, Is there a story behind the objects? What are the reasons for choosing these items?

After my initial encounter with an exploded television, the objects I use have a relationship to me that I select for a specific purpose.

One example is working with spectacles. I had recently lost a few members of my family, and when clearing out my uncle and nan’s council flat I found that my uncle had kept every pair of glasses he had ever owned. He had hoarded a variety of things but these seemed important to me in relation to him, as he was a shy, quiet man who was just content to watch life and not necessarily take part. I kept the preserved frames feeling there was something else in them. At the time I was exploring my own states of mind in segments at the time from sanity to psychosis – trying to break the stages into objects. When considering paranoia I thought about being watched, scrutinized and assessing your own, and everyone else’s’, every move. Through print I wanted to create a crucible of eyes watching so I used my uncle’s glasses: through from tiny glasses of a little boy, to a brand new pair with the label still attached that he hadn’t had the chance to wear yet, though he thought he would.

It is awkward to have relationships with the objects I use because it is easy to become too attached and precious as my process destroys the original item. But it is imperative to me that the work I make is painful and problematic, to be able to reflect the experiences it represents.

Obsession and pain through process are vital. There are no shortcuts to content when it comes to my work. I work hard. That is the foundation of my practice. When I take an easy route the work suffers and the message has no backbone to travel on. The process is arduous and begins as physically uncomfortable, pushing through to agony, because it has to be. This is not art therapy. This is not cathartic. It is painful. From a past of discrimination, violence and prejudice if I exposed my diagnosis this is a risk, and the process has to reflect that. Art therapy? Pah! My work pushes me to the brink of my hard won sanity, and my mind plays excruciating games with me to seduce me back to madness. My artwork will never be enjoyable because it can’t be. It shouldn’t be.

meat is touched [pt1], 2015, hand cut and varnished letters printed one at a time onto curtain lining, aprox 290cm x 120cm

declarationandmanifesto, 2014, hand carved letters printed one at a time onto curtain lining, 126cm x 240cm

Your large text based pieces are full of messages/thoughts or slogans like “I am not a poet”. Could you talk about these works and what these words mean to you?

Working with text has only emerged in the last three years, although the texts I use can often be much older. I work with extracts from books I have kept during a decade of psychotic episodes. The texts aren’t diaries so much as mindful mutterings and a way to excrete thoughts from a confused cacophony of sounds and images. I never wanted anyone to see them. I never thought to expose myself to ridicule. But I read them. I remind myself when I am tempted to go back what it is really like; I remind myself when I am happy I am out, what I have lost.

I’m not exactly sure when I felt brave enough to actually use them. In fact, I’m still not sure I am brave enough, due to the anxiety it produces to see anyone near them, let alone trying to read them. But if I had to give a moment for the choice to expose them it was being challenged about my work by a peer. They remarked that they couldn’t see the vulnerable quality in my art. This statement kept me up at night and had me pacing to keep up with my own thoughts. A few weeks later I was pulling out boxes of notebooks, loose papers and documents from a hiding place and ripping out pages here and there.

The first text piece was “declarationandmanifesto”. I hand carved letters and printed them one at a time onto curtain lining. In grey text is printed the unfinished “manifesto” I began writing during, what would be characterised as, a [resplendent] period/delusion of grandeur. The manifesto was to state that schizophrenics were the next stage in human evolution, and that those without the condition, the “norms”, were no more than monkeys controlled by impulse and emotion. I intended to have it published and to push for the rule of the schitzo. Black text hand printed over the top of the grey is taken from a document written a few months later: the decision on whether to medicate or not. Having realised I had separated from my emotions and that my reaction to family or strangers was equal I had to logically debate this state of affairs. Realising that family community, in evolutionary and survival terms, was a critical factor, and knowing how my condition was perceived by society, it seemed dangerous for my freedom and independence to continue down this route. But the cost! The loss of all the beauty I could see, escaping the confines of a skull into an interconnection with all events and life simultaneously, the loss of one specific visual and auditory hallucination that offered me kinship and affinity I would never know again within my terror of her, it was a high price, and a difficult choice to trade it all for a mental straightjacket.

In the final work there are no capital letters, no spaces, no punctuation – the nerves I felt creating it and relationship to the words was too urgent for that. There was no hierarchy in the sentences, no word that was due any greater emphasis than any other, it reflected the emotionless yet passionate tone it was written in. The grey and black words are printed over the top of one another to recreate the confusion of having more than your own inner voice, the urgency of getting this information out within such a slow and cumbersome process, and perhaps a small amount of personal protection and unease.

Text works since these pieces have taken many forms from books to banners. I AM NOT A POET was a banner created during a period of paranoia, where after barricading my apartment doors every evening I would sit in the densest corner of my fortification and try an think of a single sentence that could summarise every area of my life and keep my mind off the impending doom that awaited me. After months of tests and assessments “I AM NOT A POET” was the sentence. It worked in every context and became my self-portrait.

I find the way people discover their own metaphors and attractiveness in my work intriguing. In-depth metaphors are often associated with schizophrenics and their artwork but my personal experience of the disorder doesn’t correlate to this assumption. “he pierces my chest with holes like I am a microwaveable ready-meal” – I have been told this is a beautiful sentence describing love, or passion, even sex. I wrote it after watching a hallucination stab me: the careless and nonchalant manner of the attacker, the speed of the assaulting penetrations, the pops and slight resistance of my clothes and skin, and the lack of emotion accompanying the experience meant that this was exactly what it looked like to me. “meat is touched. grunts are made”. This is not a comment on sex, this was watching “norms” shake hands. I had felt for a long time that the meat (flesh/skin) encapsulating me was constrictive and repulsive; as such people’s actions with their bodies were simplified into slabs and groans in my perception.

My intrigue into watching or hearing a viewer’s reactions and thoughts lead me into my practice of endurance performances.

sheets and pages (3,4 & 6), 2014-15 , hand carved letters printed one at a time onto curtain lining

What do you hope the viewer gains/reacts from looking at your work?

I can no longer try to guide every/any viewer’s reactions or predict their responses as they always surprise me, and they captivate me. In fact my fascination with the viewer provoked a new medium into my practice that I’ll mention in a minute. However, I try to provide the unease of being able to unwillingly relate to a psychotic. I’m interested in the concept of ‘the circular spectrum’ and the cross over points between sanity and insanity. I believe the divide between the two is frail and pregnable, like laddered tights. Osmosis is certainly a pleasant threat.

My collaborations extend beyond the art world in search of human relationships that influence and enlighten new perspectives and ideas. Removing agenda and offering pure unaffected experience allows a viewer to take the perspective to do with what they will. It is an oxymoron of bringing social activism into a work while abandoning judgement or leading opinions – this allows for enabling empathy to challenge imposed dogma.

My communication is precarious between the viewer and myself. It is sadistic vulnerability-taking risks with identity, exposing intimate histories, loss of self, and presentation that provokes judgement–and fear of that judgement. A range of responses have emanated from viewers, from being laughed and shouted at, threatened, exposed to aggressive psychical responses, being confessed to, to being posed with for selfies.

I am perplexed by viewers’ reactions and their reasons for them. I wanted to find a way to watch the audience closer. My work is already self-portraiture and pushes my sanity into questionable states, so what if I could be the artwork itself and push my mind and body to it’s limits to be able to watch an audience from a privileged location. During endurance performances I stand completely still for set durations (up to 80 hours) with one or two items that I hold for the audience to figure out how to interact or activate it/me. I become "object", and the interactions that follow intrigue me. Social regulations break down solely between each individual viewer and myself. I am physically engaged with, I become a curiosity, I am ignored, and I become part of conversations people had no intention for me to hear. The mental masochism and voyeuristic element on both the side of the audience and my own becomes comfortable. When I stop and walk away it is unsettling for the viewer as I revert back from object and my humanity is restored to them; and myself.

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day/studio routine? What is your studio like?

At present my studio was previously an office in a former NHS disability rehabilitation and mental health service building. I both enjoy and detest the irony of spending my life to date avoiding these units, to then voluntarily move into one (and paying for the privilege). Formerly I would make my studio wherever I could find a space – a driveway, a loaned garage or shed, or a residency somewhere in the world. But for my new series of work I needed the time and space to be able to work on artworks for a long time, and develop the emerging ideas with both walls and a ceiling from the elements.

My day-to-day routine is not glamorous. I begin very early to get admin out of the way and then I will usually be found doing a repetitive, uncomfortable task and occasionally swearing to break the silence. I don’t listen to music or have anything around that can distract me. I have to be strict with my studio and myself and I won’t come out of my compulsive tasks or look at a clock until I’m so hungry or thirsty I can’t ignore it anymore. I am not able to work on more than one work at a time as obsession is so tied into my work that I cannot put an artwork aside until it is completed. Works that haven’t yet satisfied my obsessive needs after completion are currently being ripped up and fed to new works. This can be tough if they are frequently requested for exhibits, but if I cannot accept that I took them to their limits then they have to go back to ‘process’ for another work. I’ve realized over the past few years that if I am not confident in the piece’s process and its content then I can’t let it out to represent my experiences, and as such me.

How do you go about naming your work?

Titles are an element/skill I am still working at. I feel disappointed if I am interested in a piece of work enough to go and read the title it saying “untitled”. I spent a long time using “untitled”, or asking other people their responses to name the work, or just naming it after the objects used. None of these methods worked for me. At present I am trying and testing new methods and ideas to name them. Damien Hirst could always give a title that made the work better than it was without it, and Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ” used a title to turn the divine into the profane, there is a huge history of strong titles (and a source of envy for me). But the current piece I have been working on for the past 11 months has hope… or at least a shortlist of concepts to approach a title with. Doh.

Coming Soon, endurance performance, 6 hours duration, 2016 (photographs courtesy of Meike Brunkhorst and Lorraine Fossi)

LABELS, experiential video and sound installation, 6 hours, 2015

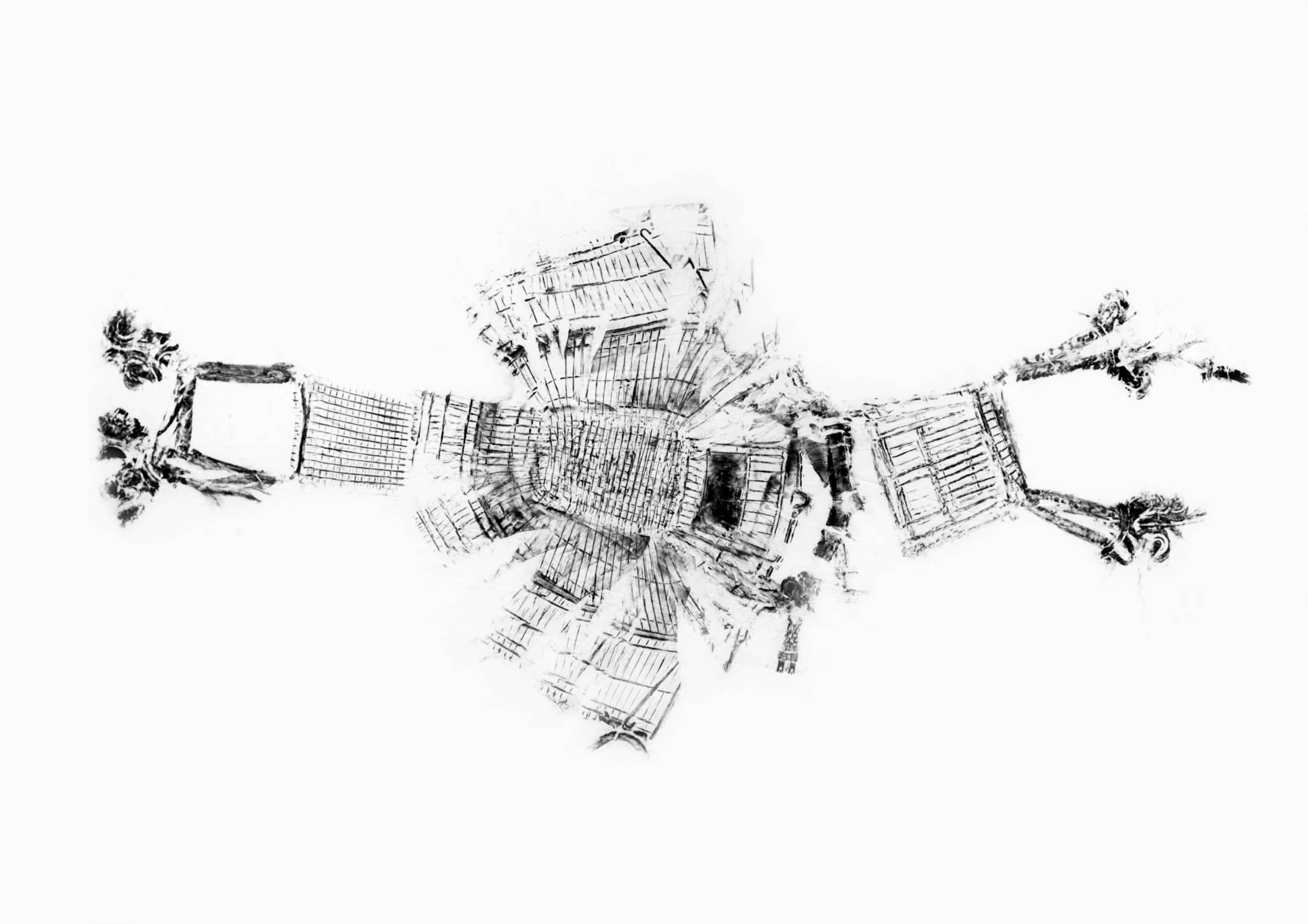

Community Project: Recession Impressions (Car Print), 2010, UNCC USA (photograph courtesy of Ken Lambla)

Dodge White I, 2010, printed dodge minivan onto fabric, 1219cm x 609cm

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

Henry Hussey’s embroidered tapestries, Christopher Gray’s puppetry videos, Mona Hatoum’s performance notes and a lot of political and military propaganda from around the world throughout history.

Henry Hussey’s work interests me for the free flowing thoughts and images that cross politics to the very personal versus the time consuming medium. The exceptional textile craftsmanship he employs satiates the trained printmaker in me, while the texts he writes and uses challenge my own practice and force me to place myself into the contemporary context and figure out where I am succeeding and lacking. The artist and artwork raises my game, rouses me to try something new and take a risk. I appreciate that after and beyond my admiration of the work.

Christopher Gray I have no doubt is going to be the next art world superstar. I was lucky enough to exhibit with his at Griffin Gallery and Charlie Smith London, and I’ve followed his work through to winning the Catlin Art Prize. His recent video torture scenes involve creating puppets from chicken carcasses, cracking bones and sewing up skin; studying movement so that his hands can bring his silent (when not screaming) characters to life; creating intricate sets where his face is always visible when he forces his hands to commit atrocious acts on one another; to knowing he asked his daughter to do the filming.

The violence and gore creates palpable tension in a room, and I’ve watched audience members have to walk away in horror and disgust from the violence, even though it is evident from the puppeteers face and hands in shot that it is fictional, almost playful. To have that sort of contradictory impact is remarkable.

Mona Hatoum’s solo show at the Tate Modern was a highlight this year to be able to see works in real life that I have looked at on a computer screen for the past five years. I hadn’t realised prior to the exhibition that she had also been a performance artist, and reading the plans, documentation and transcribed events opened up a deeper understanding of such an influential artist. It is easy to enjoy but be underwhelmed by retrospectives of artists who are so famous and artworks that have been highly reproduced, but the additions of test pieces, sketchbooks, written performance plans and notes added a reality to the polished public image distributed by galleries and the Internet.

Finally, propaganda. I am exploring empathy at present through multiple routes: neuroscience, philosophy, theory, sociology and affective technology. As such my paths have crossed with propaganda, and campaigns that have sought to impose their opinions on the collective, rally the masses to a ‘shared’ cause, gain power or achieve specific outcome through other peoples’ action. The spin off achievements of advertising or present day media is no less interesting or terrifying. With a project I am leading working with with a drug compound scientist, anthropologist, inventor and some fellow psychotic voyagers, I am pondering what this knowledge might assist us to achieve.

Young Gods, Griffin Gallery, 2016 (photograph courtesy of Griffin Gallery)

What does the future hold for you as an artist? Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

Studio time and some upcoming exhibitions are on the cards. My work is currently in the final stages of consideration for Neo Print Prize and summer studio visits are in full swing. I’m working to complete my current art piece and body of research that I began eleven months ago that explores if psychotic and sane individuals are the same during sleep. I have had nightmares every night since I was a child; with two of my three earliest memories being nightmares. When looking into historical diagnostic tools for psychosis when researching a paper on the history of “insane art” and its segregation I found that constant nightmares were often an indicative factor.

When I chose to medicate my nightmares never stopped, even though my waking hours were altered dramatically. Am I still a schizophrenic in the dark, and are you too?

As for further in the future I couldn’t say yet. Some investigations into inventing a new affective technology are being drawn up and scribbled down in notes, I have a set of chisels that are distracting me, and I would like to revisit my tape-recorded for some sound work, but I think the culmination of my current art piece will spark enough new questions to provoke a new work. I have a tendency to act very quickly once a dominant idea emerges.

Publishing date of this interview: 12/08/16