Steph Goodger

"the subjects may be the dead, confined to their boxes, but the paint itself has life which defies death in a sense, even when depicting it."

Could you tell us a bit about yourself. How long have you been a practicing artist and where did you study?

I first studied at what is now the University for the Creative Arts, Canterbury, when I was sixteen. It was a new course, a BTEC Diploma in Art and Design. In the second year I specialised in painting. The conceptual considerations went totally over my head at that stage, but I loved listening to discussions that seemed like a foreign language at the time.

After that I did a BA at UCA Farnham. At twenty-one I spent two years in Newcastle Upon Tyne, mostly on the dole or working as a life model, and painting. Then I came back down South to do a two year, part-time MA at Brighton University. Oddly, I gave up painting half way through and started writing prose poems. I finished the MA but it was several years before I began painting again. When I did, it was totally different. A whole new range of possibilities seemed to open up, relating to narrative. I have never stopped painting since then.

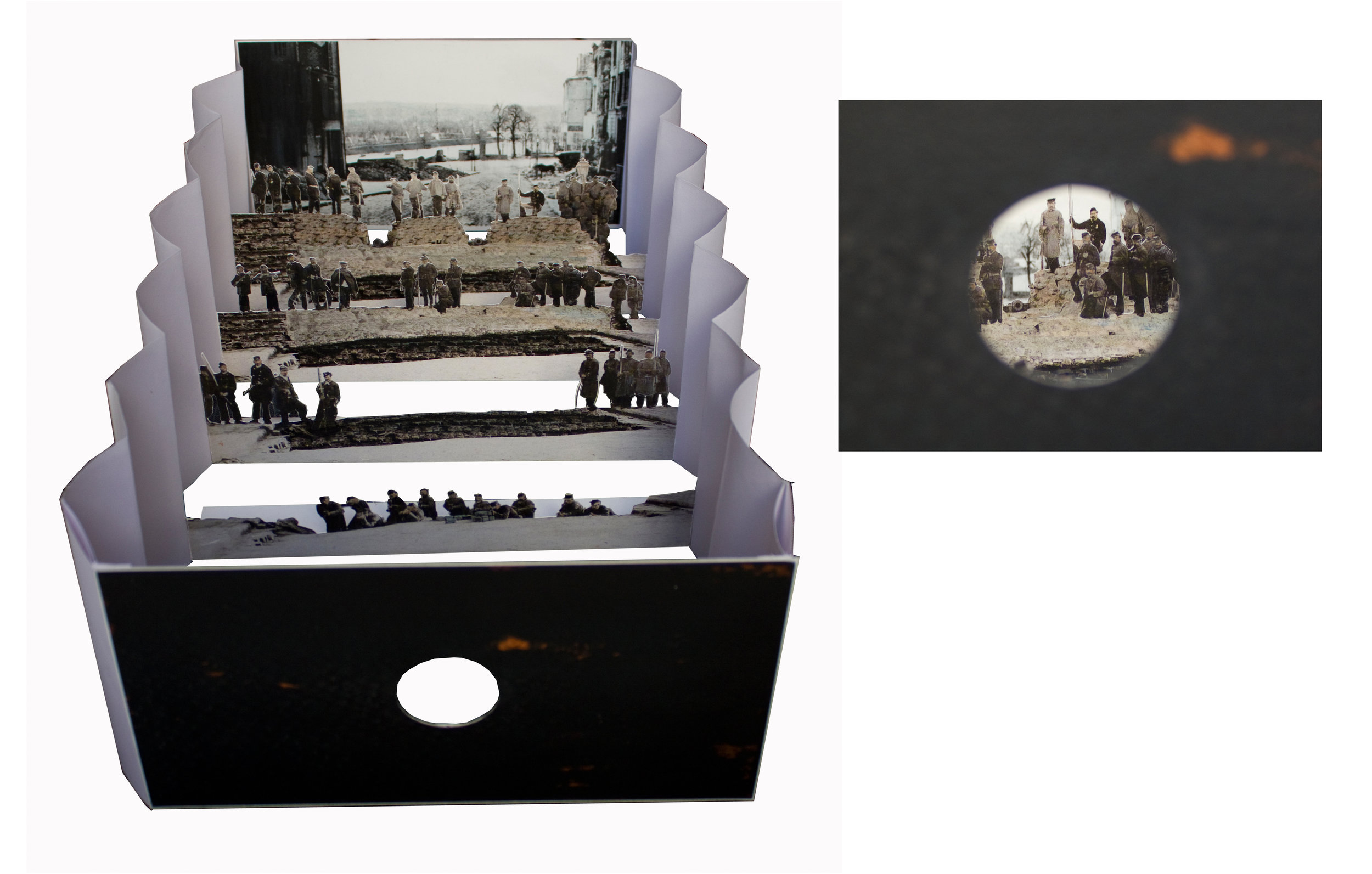

Barricade Parade, 2016

The series of paintings titled “Les Non-reclames” (The Unclaimed) depict dead figures inside coffins, could you tell us a bit about these pieces?

Les Non-réclamés (The Unclaimed) title comes from the title of an anonymous photograph, Insurges (Insurgents) Non-réclamés, 1871. Another, extremely similar photograph, by Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, is entitled, Communards in their Coffins, 1871. Both depict groups of twelve dead men in open coffins, lined up in tiers. Each man has a white paper with a written number on it, laid on his chest.

The men have obviously met violent deaths in some conflict, apparently the Paris Commune. The Commune was a short-lived uprising against the French government, following the Franco-Prussian War, and lasting only two months. Disderi’s image especially, is like a morbid school photograph, very carefully composed, with the anonymous dead standing vertically, side by side, together yet apart, in their crudely hewn, open boxes.

They could be the 'sans-nom', the non-heroes, from any scene of conflict. The absence of identity and ultimate meaning, go hand in hand with the absence of life, or, as Roland Barthes describes it in Camera Lucida, 'the presence of absence'. The photographs are a compositional jumping-off point for the paintings. Painting, I find, is an ongoing tussle between containment and release. In, Les Non-réclamés series, the subjects may be the dead, confined to their boxes, but the paint itself has life which defies death in a sense, even when depicting it. There is also the dichotomy between the sense of the group, their community, and the individual, alone in the last space he will ever inhabit.

I’m interested too, in reproducing Barthes’ ‘presence of absence’, somehow. I love the notion that absence could have a presence of some sort in the painting. Then there are all the intriguing details in the photograph, clues to identity but no answers; the blatant horror of the wounds; and the general poignancy of it all. It’s quite an overwhelming subject really.

Les Non Reclames, 2015

no 11 and no 3 diptych, 2016

Many of your paintings are staged in a certain part of history (mainly 1800s), could you tell us the reasons for this? What draws you to this era?

I’m drawn to subjects which have been in some way censored, hidden away because they are an embarrassment, or for fear of social unrest and ultimately revolution. The development of socialism, the prison system and systems of containment in general, all interest me. The prison hulks (prison ships) of the 19th Century became a huge project; and then the Paris Commune, which was for Marxists a precursor to events in Russia, even though it actually achieved very little at the time.

The past is like a place to go to see the world I live in more clearly. My colleague Julian Rowe said, ‘I regard history as the deep present, the present in its proper context.’ History is also a rich source of ideas and images, creating a platform from which to make work.

My interest in staging and re-staging is central. A painting for me is a form of staging, so what other forms are out there? That’s how the 19th Century invention of the paper Peepshow theatre first attracted me.

Less explicable is the fact that certain objects and images just jump out and literally grab me visually, and two years later I still can’t put them down, such as, hulks, barricades, the coffin images, and more recently mourning lockets. The work orbits around several over-arching themes, of containment/confinement, war, death, mourning and mementoes. I ultimately want to share how I am touched by the poignancy of events, both historical and current. The tragedy in peoples’ lives is important, but for something to be very poignant, it also has to contain elements of the odd, the absurd or the amusing.

The Album, 2016

How do you go about naming your work?

Sometimes a title comes simultaneously with an idea or image. Les Non-réclamés, for example, came from the title of the photograph I wanted to work with. Literature provides many titles. Splendid Isolation, for example, was born out of reading about British foreign policy at the height of colonialism. This was for a project based on Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Voyage.

The title for the dead birds triptych, How they Might have Danced, came from the Dylan Thomas poem, Do not go gentle into that good night. Cherry Time, the title of my current exhibition with Julian Rowe, is also the title of a French song, Le temps des cerises. The song became the anthem for the Paris Commune, and is still an extremely well know revolution song in France.

But sometimes I simply have to call a spade a spade; Hulks, Barricades, Boxcars, Mourning Lockets. I prefer to keep things simple, unforced. A title should resonate naturally with the work I think.

What do you hope the viewer gains/reacts from looking at your work?

Bizarrely, a lot of people expect me to be a man when they meet me. Which I guess goes to illustrate how social and cultural mores can influence the viewer, and the artist for that matter! There is so much which is beyond the artist’s control in that sense. So I don’t have any precise hopes as to what the viewer gains or how they react to the work. It’s the general dialogue around the work which makes it worthwhile. If it generates any kind of discussion, interest or emotional response, I’m extremely happy.

It’s also important for me to communicate ideas as objectively as possible through the work. There is never any political objective to convince others of anything. It’s simply a case of intention, doing what I intend to do, as clearly as possible, then it’s out there. If I’ve got it right, the viewer might even feel the power of painting to transform, to make things happen in ways nothing else can. That’s the main thing.

Cherry Time (installation shot), Elysium Gallery, 2016

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

Kiefer at the RA in 2014 was the most intense experience I’ve had at an exhibition, since I stood in front of Géricault’s, Raft of the Medusa, for the first time. The sheer power and energy of the work felt like it was crushing me. He grants himself total freedom, and there’s an absolute sureness about his execution. He tackles the big themes of existence with a sort of physicality that goes by its own aesthetic logic, transcending any external expectations we might have. All the way around the show I thought, that’s how it’s done!

Next to Kiefer is Julian Rowe (he’ll like that!), my long term collaborator. Our current project, Cherry Time, at Elysium Gallery, Swansea, is running until 8th October. We have been working towards this for over a year now, sharing research and having long talks. It’s a collaboration at a distance, as he lives in Kent. The results of our combined research are superficially very different, but something happens when the work is put together, like a call and response, the artist Tim Kelly put it, which creates a kind of visual coherence.

Louise Bristow is an inspiring artist for me, with her practice of making models which she then paints from. This resonates strongly with my practice of making models for paintings; a model Raft of the Medusa, a whale skeleton and recently the Peepshow theatre.

Louise’s models are very different from these. They are amazing, like three dimensional paintings and her paintings are like models. But I relate to the rapport between the two, and that intended sense of artificiality which the model brings to the painting.

Eric Manigaud’s drawings are incredible. He’s not frightened to tackle very difficult subject matter, which I find encouraging. I have been working recently from images of early photojournalism, war and morgue photography, so I think I share his interest in certain subject matter.

At the John Moores Painting Prize this year I discovered many fascinating works. There were two which resonated with me specifically. Talar Aghbashian’s, Untitled, refers to scenes of destruction of historic monuments, with the broken hand as a sort of emblem of conflict. In Duncan Swann’s, I choose the child, figures are painted with dramatic tonal contrast and fluidity, inhabiting what he calls a non-space. They are in some way classified and selected, by an unknown system. This is exactly what I see in the Non-réclamés photographs, with the mysterious numbers on the dead men’s chests.

Peepshow Theatre, 2016

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day/studio routine? What is your studio like?

When I’m working I do weird dancing and talk to myself, so there’s no possible way I could share a studio, or work in a group situation of any kind. I would feel inhibited somehow.. My current studio in Bordeaux is a very private place really. There are two main areas. There’s a cosy back room with a large, old, wooden table, where I make small work, or do anything which requires a clean environment. The other room is a large garage with a broken up concrete floor. I had to install glass frontage, which makes it a really light space now. The children who live in the street come and press their noses to the glass and watch me work.

There’s usually a large work on the go, around 3-4m in length, on the main painting wall. There’s a step ladder, a couple of tables for paint, and photocopies of the images I’m working from, or small drawing, spread out all over the floor. There are often several other works on the go in there too, which get moved around, depending on space requirements. In the back room there are books, magazines, and a radio. I’ve been making some 10cm x 8cm paintings of mourning lockets on the big table in there recently. The two rooms give me very different feelings, which seem to complement each other. Both are necessary.

What does the future hold for you as an artist? Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

The Museum of Art and History at St Denis, Paris, is kindly giving me access to their archives relating to Nicholas Kohl’s, Vitrine of a Terrible Year, July, 1871. It’s a cabinet displaying objects like relics, fifty-seven in all, which Kohl apparently collected during the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune. It contains the bones of the mice and rats they were forced to eat when Paris was under siege; bits of the sawdust bread they had to make; debris from ruined buildings; medals; Prussian money; and other extraordinary objects. I hope to create some paintings relating to the Vitrine and the mysterious figure of Kohl himself.

Another project in the pipe-line, including more Peepshow work and paintings, relates to European Colonial Fairs and anthropological zoos, from 1850's until 1930's. This is another research project with Julian Rowe, leading to a new body of work.

I’m also working on a screen print for, The Arca Project, to be exhibited at PayneShurvell Suffolk, in March and April next year. The project is curated by Michael Hall at Invisible Print Studios, Wimbledon, and Graeme Gilloch. Fuelled by Michael and Graeme’s shared obsession with W.G.Sebald, The Arca Project consists of 15 visual and 15 textual responses to one single image. Each response will be realised as a poster edition.

Interview published: 30/09/16